Before an unemployed sicko changed tennis history and got away with it; before he walked down through the stands in Hamburg, Germany, and past a crowd distracted by a changeover; before he leaned over a 3-foot barrier and plunged a 9-inch knife between her shoulders, Monica Seles was not only the best women’s tennis player in the world. She was also the toughest.

No one knew from where the toughness sprung except Seles herself; she once explained that she so dearly loved the game from such a young age that it never occurred to her to be nervous, or care about who was winning, or even understand how to keep score.

“Mentally she was just so tough, she was right up there with Chris [Evert],” Martina Navratilova said of Seles in a recent phone interview. “You couldn’t crack her, you never got the feeling she was panicked or pissed off. Nothing. You could not read her body language. Up 6-4, 4-0 or down 6-4, 4-0, she was immaculate, and she lost a little bit of that, not hardness, but supreme confidence. … She lost her edge.”

Monica Seles lost a lot more than that.

Once a legitimate threat to break Margaret Court’s record of 24 Grand Slam singles titles; once a source of constant frustration to Steffi Graf, who is No. 2 with 22 Slam wins; once one of the toughest competitors in all of sports, Seles didn’t just have her career altered on that awful day 20 years ago. It was stolen from her.

“I can’t say whatever was meant to be, was meant to be,” Seles told me in a 2004 interview with the Chicago Tribune. “When I look back, I’m sure my career, in terms of achievement, would’ve been different if I hadn’t been stabbed, and I’ll always wonder why I’m the only one in history who that ever happened to.

“But that was the course my life took, it was beyond my control, and I have to let it go. I don’t want to think what could have been, what would have been.”

And so, short of a few pages in her 2009 book “Getting a Grip,” in which she wrote about the attack, she has slowly stopped talking about it altogether. And a publicist promoting her upcoming book, part of a teen series Seles has written for Bloomsbury Children’s Publishing, politely turned down an interview on behalf of Seles because of the subject matter.

You can hardly blame her.

Ahead of her time

Turning 40 this year — a hard fact to absorb for those of us who remember her so well at 15, the year she turned pro, and at 16, when she won her first Grand Slam title — Seles was always ahead of her time.

Possessing the most recognized and successful double-fisted forehand in tennis, along with a top-flight two-handed backhand, she was also the original grunter — though tame by today’s standards. But that was how Seles used to be defined before becoming the only known professional athlete to be stabbed in the arena of play.

“

The most shocking events in my 35 years-plus of playing tennis was the day Vitas Gerulaitis died; the day it came out that Arthur Ashe was HIV positive and the day he died; and the day Monica was stabbed. Those were all days where I very clearly remember where I was. … What happened to Monica was almost unthinkable.

”

— longtime pro Pam Shriver

“The most shocking events in my 35 years-plus of playing tennis was the day Vitas Gerulaitis died; the day it came out that Arthur Ashe was HIV positive and the day he died; and the day Monica was stabbed,” said longtime pro and Seles opponent Pam Shriver, an ESPN analyst. “Those were all days where I very clearly remember where I was. … What happened to Monica was almost unthinkable.”

On April 30, 1993, Seles was playing in the quarterfinals of the Citizen Cup, a tour event in Germany, on an otherwise perfect day. After winning the previous four games, Seles was leading Magdalena Maleeva 6-4, 4-3 and seemingly poised to close out the match.

At 19, Seles was the top-ranked player in the world and in the prime of her career. She had reached the finals in 33 of 34 tournaments from January 1991 to February 1993, winning 22 singles titles. More astounding? She had won eight Grand Slam tournaments from 1990 to that point, with a match record of 55-1 in Slams.

At 23, Graf had won 10 Grand Slam titles by April 1993, and until ’91 had had a four-year stranglehold on the No. 1 ranking. But in ’91 and ’92, Seles had surged ahead, and she defeated Graf in a dramatic three-setter in the ’93 Australian Open final, three months before Hamburg.

With Evert having retired and Navratilova nearing the end of her career, Seles and Graf had clearly separated themselves from the rest of the pack and were primed, it seemed, to develop a rivalry on the level of Navratilova-Evert, Jimmy Connors-John McEnroe and Pete Sampras-Andre Agassi.

“We got cheated, Monica got cheated, everyone got cheated,” Navratilova said.

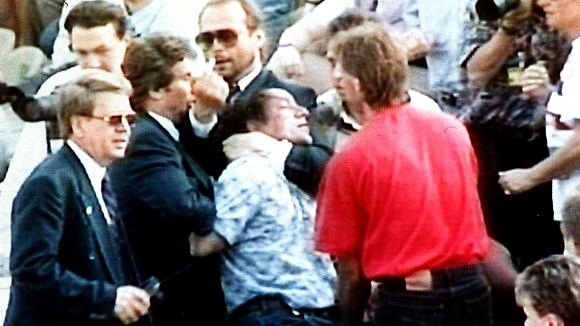

Gunter Parche, an out-of-work, 38-year-old German factory worker obsessed with the German-born Graf, would have stabbed Seles a second time that day in Hamburg but was wrestled away by fans and officials before he could inflict further damage. His motive? Parche admitted he wanted to keep Seles from playing at a high level so Graf would be No. 1.

Gunter Parche was given only a suspended sentence and probation despite stabbing Monica Seles in the back during a match in 1993.

At first, many in the crowd were unaware of what had occurred. Seles gave out a yelp as the blade plunged a full inch and a half into her upper back, but she stayed on her feet for several seconds before slumping, with the help of officials, to the court.

“I remember sitting there, toweling off, and then I leaned forward to take a sip of water, our time was almost up and my mouth was dry. The cup had barely touched my lips when I felt a horrible pain in my back,” Seles wrote in her book.

“My head whipped around towards where it hurt and I saw a man wearing a baseball cap, a sneer across his face. His arms were raised above his head and his hands were clutching a long knife. He started to lunge at me again. I didn’t understand what was happening.”

Physically, Seles was incredibly lucky, as the knife barely missed her lungs, spinal cord and other major organs. Miraculously, she needed only a few stitches to close the wound and a short hospital stay. But the pain, she said, remained for months. And the torment?

Depression in aftermath

In her book, Seles said she spiraled into a deep depression that manifested itself in an overeating disorder she had never before experienced.

Describing her attempts at rehab, Seles wrote, “Even 10 minutes of walking was torture. I just didn’t want to do it. What was wrong with me? There was a problem that no CAT scan or MRI readout could diagnose. Darkness had descended into my head. No matter how many ways I analyzed the situation, I couldn’t find a bright side.”

Seles would end up being out of tennis for nearly 28 months. During that period, the WTA, the governing body of women’s tennis, consulted with its top 25 players and refused to freeze her ranking points.

“As I remember it, in the short history of the rankings to that point, they had never been manipulated to freeze anybody’s or take someone off,” Shriver, then-president of the WTA Players Association, said by phone. “They were what they were. But this was a precedent-setting event and we needed to have some different thinking and consider new options.”

Graf went on to win the next four Grand Slam tournaments — the ’93 French Open, Wimbledon and U.S. Open and the ’94 Australian Open — and also agreed to an endorsement deal Seles said she was close to signing before the attack and regained the No. 1 ranking five weeks after the stabbing.

Fall from glory

Seles would never be No. 1 again.

“She had won seven of eight Grand Slams [from ’91 to ’93] and was on her way to doing even greater things,” recalled Mary Joe Fernandez, a 15-year veteran of the tour, ESPN analyst and Seles’ closest friend to this day. “She was robbed. It was one of the most tragic things to happen in all of sports.” Monica Seles defeated Martina Navratilova in this women’s semifinal at Wimbledon on July 2, 1992, when Seles was at the hieght of her success.

“She was dominating Steffi Graf, who, prior to Seles, dominated everyone else,” Shriver said. “The sad thing about the whole thing to me was that besides the physical and emotional harm that was done to Monica, one of our great champions, is that this guy, in the end, got exactly what he wanted.”

Further hindering Seles’ recovery was her beloved father Karolj’s cancer diagnosis (the disease led to his death in May of ’98) shortly after Hamburg and, less than five months after the stabbing, the trial of Parche.

Despite Parche’s confession and the hundreds of eyewitnesses who saw him stab Seles, an attempted murder charge was dismissed. He was found guilty of the lesser charge of committing grievous bodily harm and was given a suspended sentence and probation. The judge believed a psychiatrist who testified to Parche’s diminished capacity and also credited Parche for his full confession and ultimate show of remorse.

Unable emotionally to attend the trial — “How could they have expected me to go back [to Hamburg],” Seles said later. “I mean, I would have had to sit in the courtroom with my back to him” — she instead sent a letter that was read in open court.

“I only want proper justice,” it read in part. “This attack irreparably damaged my life and stopped my tennis career. . . . He has not been successful in his attempt to kill me, but he has destroyed my life.”

Nineteen months later, a new judge upheld the verdict, citing Seles’ refusal to testify as a determining factor. The WTA released a statement strongly condemning the German court for sending “a terrible message with wide-ranging impact.” Seles collapsed in tears in front of reporters when being told of the verdict and later said she could not stop crying for days.

“I think that [got to me] more than anything, that there was no kind of punishment,” Navratilova said. “The judge was like, ‘Oh, he won’t do it again so I’ll let him go so he can really kill someone.’ It was insane and so nationality driven. If someone had done that to Steffi so Monica would win, they’d have thrown away the key.”

The repercussions

It was theorized at first that the crime was political in origin because of what many misidentified as Seles’ Serbian roots (in fact, her family, which had lived in Florida since 1986, was Hungarian but came from a village near Bosnia, controlled by Serbs).

In the end, however, it was simply a tragic case of a deranged fan wanting to hurt his favorite’s rival.

Seles never played in Germany again.

As for Graf, who has attracted her own share of crazy fans, she went to visit Seles in the hospital days after the attack and hours before winning the Citizen Cup singles title. Graf has seldom spoken of the incident publicly and did not respond to interview requests.

“The whole thing must have been, and still must be, a huge burden to carry [for Graf],” Shriver said.

Navratilova was not quite as understanding.

“I’m sure it shook [Graf] up, but she won a lot more than she would have otherwise,” Navratilova said. “If it affected her that deeply, she would have forged a stronger bond with Monica instead of ignoring her. It was nice initially [for Graf to see Seles in the hospital, a visit Seles later described in her book as lasting ‘a few minutes’], but after that?”

Either way, there is no denying the stabbing reverberated through the sport.

“She got stabbed in her office,” former No. 1 Jim Courier said in a British documentary about the attack a decade later. “Can you imagine being in your office and someone opening the door, coming up behind you and sticking a knife in your [back]?”

Though rules changed immediately, with tighter protection around players during matches and their chairs turned to face the umpires and crowd, no one could erase what had happened. Navratilova described a lost sense of security after the attack.

“A couple times I had death threats at tournament, so I had to have bodyguards,” she said, “but when you play a match, you’re out there. Anyone with a rifle can get to you, so you are vulnerable. But this kind of attack would never occur to you.

“To me, the tennis court was an escape from all the good and bad things happening in my life. When things are going well, you’re happy, playing the game you love. When things are going badly, it’s a great escape to do the thing you love. But either way, you’re in a total safe zone in the place you want to be. For this to happen was such a shock. You just felt extremely vulnerable.”

Seles’ return

After Seles returned to the tour, the WTA reversed its earlier decision and reinstated her No. 1 ranking, to be shared with Graf for six months. And at first, Seles appeared to have regained her old form, reaching the ’95 U.S. Open final against Graf.

But Graf won in straight sets, and though Seles won one more Grand Slam title — the ’96 Australian Open — she would never recapture what she once had. Just as alarming for those who followed her career, she would never again display the same sense of innocence coupled with a steely confidence that so dramatically set her apart.

“She would have won so much more,” Navratilova lamented. “We’d be talking about Monica with the most Grand Slam titles [ahead of] Margaret Court or Steffi Graf. Steffi had 22 [Navratilova and Evert have 18 apiece], but she didn’t have anyone to play against. This guy changed the course of tennis history, no doubt about that.”

“People forget,” Fernandez said. “If you look at [Seles’] record, she has nine Grand Slams, which is an amazing career. But she would have had double that at least. . . . She took our game to another level.”

Seles’ last competitive match was at the French Open in 2003, but she would not formally announce her retirement until 2008, the same year she became a contestant on “Dancing with the Stars.”

In 2009, she was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame.

Fernandez said that today Seles is “doing great. I don’t think I’d have ever played again. The fact that she returned to the court was amazing. And then to win a major again shows just how strong mentally she was to put that behind her.”

The woman Fernandez describes is still charitably driven, particularly with causes involving children and animals. She is still very close to her mother, Ester, and her older brother, Zoltan, who rode with her in the ambulance that day in Hamburg and held her hand. And she is a thoughtful friend, never forgetting Fernandez’s children’s birthdays.

“She’s a very well-adjusted woman, smart, caring, one of the best women I know,” Fernandez said. “She’s considerate and a really good person, which shows her character and reflects her upbringing by great parents.

“She has been able to move on and create a great life for herself. [The attack] is something that will always be there, unfortunately, but Monica is strong like she always has been.”

Melissa Isaacson

Columnist, ESPNChicago.com